Sculpture Drawings

I’ve long enjoyed drawing classic and baroque sculpture. In fact my project as a Visiting Artist at the American Academy in Rome was doing just that on three occasions. In additional trips to Italy my pursuit continued. I’ve always felt that the most appealing part of making art is the magic that happens when a three-dimensional form is converted to a two-dimensional surface convincingly. A magical feat.

What better opportunity for exploring the possibilities of capturing form than with sculpture? For one thing, the “model” never moves! And never asks for payment! Eventually, I came to realize that right here in New York, we also have some pretty spectacular specimens. At first, I focused on one of my favorite pieces, “Ugolino and His Sons” in the Petrie Court at the Met. The resulting eight large charcoal drawings have been on display in the lobby of the 13th Street Repertory Theatre for nearly three years (see “The Ugolino Series” in the Journal section of this site).

The following drawings were done, mostly, right here in the City. Whenever possible, I start by doing a rough sketch from “life.” The locations of some of these pieces often make this an unreliable possibility, in which case I skip that step and just take a quick, down-and dirty iPhone shot. And that’s what I use for reference as I draw. Occasionally, when I find an inspiring piece in an online photo, I use that.

Mater Dolorosa

I’ve long enjoyed taking iPhone shots of sculpture at the Met in order to turn them into large drawings in charcoal pencil. In 2014 the museum treated us all to an exhibition of work by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-1875). Among them, this bust of “Mater Dolorosa.” The sculptor died of bladder cancer at the age of only 48, it’s said having been blinded by plaster dust toward the end of his life. Dolorosa indeed.

Diana the Huntress

During the Covid pandemic it was a great pleasure to have some projects. One of them was to make a drawing of this magnificent marble sculpture from Berlin’s Bode-Museum by Bernardino Cametti, created in Rome in 1720, from a photo found online.

Amalthaea and Her Goat

Certainly at the top of my list of “Best Birthday Presents Ever” was a trip to Montreal with my son, daughter-in-law and two grandchildren. We visited the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts while there, and came upon this wonderful work of sculpture by Pierre Julien, created in 1876, “The Nymph Amalthaea.” Seems that the mother of gods, Rhea, had a real problem. Her husband, Cronus, kept eating their babies, since he believed that he’d be eventually overthrown by one of his children. So when Zeus was born, she cleverly whisked him away to this nymph to have him nursed by her goat.

Andromeda and the Sea Monster

The Petrie Court at the Met houses an incredible array of masterpieces, this one very prominently placed by the entrance. It was created in 1694 by Domenico Guidi. I made this drawing in the early days of the Covid pandemic, before the country house exile. The sculpture drawings in this section are all quite large, requiring an easel, which I only have in the New York City studio, so this will be the last entry here for a while.

Struggle

This one is not here in the United States, but in Rome at the National Gallery of Modern Art. Modern Art, you may well ask? After posting this on Facebook, a friend commented that the Italians call modern art anything that was created after the country became unified in 1861. This incredible piece was completed by Gaetano Cellini in 1908, not the 1600s as I would have guessed. He called it “The Fight of Man Against Evil.”

Three bas reliefs from the Metropolitan Club:

The next three pieces are a total mystery to me. I’ve searched the internet for information, but to no avail. I was invited last summer to attend a lecture at the Metropolitan Club by the author of a biography on Sandra Day O’Connor. I sat at a table right in front of the podium. The talk was brilliant, but I kept being distracted by this amazing work of art behind the speaker. It was hard to concentrate with such a strange and beautiful presence capturing most of my attention. After the event concluded, I realized that there were two more of these bas reliefs in the room, all on the subject of mythological figures. I took iPhone shots of them, and was compelled to turn them into large drawings. I tried to find out the name of the sculptor, or anything else about them, but all I could learn was the name of the room’s interior designer, Gilbert Cuel, who completed his work in 1891. As to my drawings, in each case I chose to leave them “unfinished,” feeling that the illusion of three-dimensions was enhanced by the presence of the flat grid

Sphinx

Amor/Cupid

Goddess

_____________

Mercury Atop Grand Central

In some instances, the sculpture is very highly situated above the sidewalk, as in this case. This one is atop the entrance to Grand Central Station. When I enlarged my iPhone shot, the sculpture was so tiny that it appeared completely pixelated. I had to find images on the internet. Of course the photos I found online were all from different angles, and the lighting varied greatly from one to another, so it was necessary to take a piece from this and a piece from that. But in most cases I’m able to work from my own shot.This elaborate sculpture called “Transportation” or “The Glory of Commerce” was designed by Jules-Felix Coutan of Paris in 1914. Appropriately, Mercury is the god of both travel and commerce. It’s 48 feet high and weighs 1500 tons. Underneath Mercury is the world’s largest example of Tiffany glass, at 14 feet in diameter. The grouping, although designed by Coutan, was constructed and assembled by William Bradley and Son of Long Island City. Amazingly, Coutan never set foot in the US, thus never even saw his completed masterpiece. My favorite factoid is that the clock’s number 6 is actually a window that opens to reveal a view of Park Avenue!

Alice and The Mad Hatter

Most children in New York City know this landmark very well. In pleasant weather, it’s hard to find a moment when multitudes of them aren’t swarming all over the characters in this statue, as I found out when I tried to take an iPhone shot without them. The sculpture was created by the Spaniard José de Creeft in 1959, commissioned by Central Park’s benefactor George Delacorte. I’ve always been particularly drawn to the Mad Hatter, who dominates my drawing. It’s said that his depiction in this piece is an actual caricature of Delacorte! Clearly, de Creeft can’t be accused of seeking to flatter his patron.

Alice and Dinah

Not to be outdone, I had to make a drawing from the other side of the sculpture, starring Alice herself. A special note of nostalgia about the view: when my son was a toddler, he couldn’t resist sitting on her lap, as did so many of New York’s youngsters.

The Rape of Polyxena

charcoal pencil—27″ x 21″

charcoal pencil—27″ x 21″

On a trip to Florence in 2015 with the family, we had the good fortune to stay in a magnificent AirB&B on the Piazza della Signoria, right next door to the Loggia dei Lanzi. These were our troublesome neighbors. It would have been impossible not to draw them. The sculpture is by Pio Fedi, 1865.

A Lion In Winter

The marble lions, Patience and Fortitude, flank the Fifth Avenue entrance to The New York Public Library. They were modeled by sculptor Edward Clark Potter and carved from pink Tennessee marble by the Piccirilli brothers in 1911. The Lions’ best-known nicknames, Patience and Fortitude, are credited to Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, who told a reporter, ”The people of this city have two cardinal virtues, Patience and Fortitude.” On a personal note, I was flattered and delighted that the Library chose to use my drawing for its 2018 holiday card, with the help of the agents at Pippin Properties. These cards were sold out before Thanksgiving! I was told that it was their best-seller of the season, and happily they plan to do an additional printing in ensuing years.

Santa Veronica

A change of pace here. This magnificent piece of sculpture isn’t in New York City, or even in this country, but it’s so beautiful that it was irresistible to draw. It was created as a stucco model by Francesco Mochi in 1629. A contemporary of both Bernini and his father, he was a master bronze caster as well as a sculptor. This depiction of Santa Veronica, veil in hand, was carried to St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome in 1639 in three sections, after delays in securing a suitable block of marble for the final statue.

Alma Mater at Columbia

The campus of Columbia University in Morningside Heights features some fascinating sculpture. This is called “Alma Mater,” which means “nourishing mother.” It’s the work of Daniel Chester French, was installed in 1901, and has come to be the symbol of the institution. I chose to depict her from the rear, largely because I was struck by her position across the way from the engraved names of the greatest philosophers in history. Someone asked me whether she was supposed to be a goddess. I replied that I preferred to think of her as a sort of orchestra conductor presiding over the dissemination of knowledge at its highest level.

Amor Caritas

This particular iteration of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ “Amor Caritas” is housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and officially entitled “The Angel of Purity.” Saint-Gaudens first explored the composition as early as 1870, but his most famous version in bronze is housed in Paris’s Musée d’Orsay. Quite a number of these bas reliefs are in other locations, including the Met. This marble rendition was commissioned by a Philadelphian donor to commemorate the loss of his daughter in 1902.

Angel at Bethesda Fountain

New Yorkers know her well, “The Angel of the Waters” at Bethesda Fountain in Central Park. Her creator, Emma Stebbins, was the sister of Henry Stebbins, the president of the Central Park Commission at the time, 1873. A pamphlet produced for the dedication of the statue revealed the subject to be a healing angel. According to the Gospel of Saint John, the pool of Bethesda could miraculously cure illness, and must have seemed an appropriate theme to Stebbens, who had recently lost a dear friend in spite of their attempt to cure her breast cancer with “healing waters.” I’m told that in Christian theology, angels and archangels are male, but this one is clearly female.

Atlas at Rockefeller Center

The iconic Atlas in front of Rockefeller Center, right across the street from St. Patrick’s Cathedral, has to be one of the world’s most often photographed statues. It was created by Lee Lawrie in 1937. Reference materials say “with the help of Rene Paul Chambellan,” presumably meaning, as so often seems to be the case with sculpture, that Lawrie produced a maquette, and Chambellan did the actual carving. I wouldn’t usually be particularly enthusiastic about drawing such a highly stylized piece, but this Art Deco masterpiece was unavoidable.

The Thinker at Columbia

Auguste Rodin’s “The Thinker” was originally designed in 1880-82 as the central figure at the top of his monumental set of doors, “The Gates of Hell,” intended to represent Dante contemplating his journey into the inferno. Rodin cast his first life-sized versions in 1903. After Rodin’s death in 1917, his studio continued to produce bronze casts in his name using the sculptor’s original models. Columbia’s replica was cast in bronze by Alexis Rudier, Rodin’s preferred foundry. Appropriately, the sculpture has been situated on the lawn outside Philosophy Hall since its commission in 1930.

Washington at Federal Hall

In 1882, John Quincy Adams Ward’s bronze “George Washington” statue was erected on the front steps of Federal Hall, marking the approximate site where our first president was inaugurated. The sculpture is often overlooked by tourists, it’s said, because the charging bull a few blocks away commands so much attention. In order to take this iPhone shot, I had to stand, virtually, underneath it, since the piece is mounted on a perch just above the sidewalk, but extreme angles are always intriguing to me.

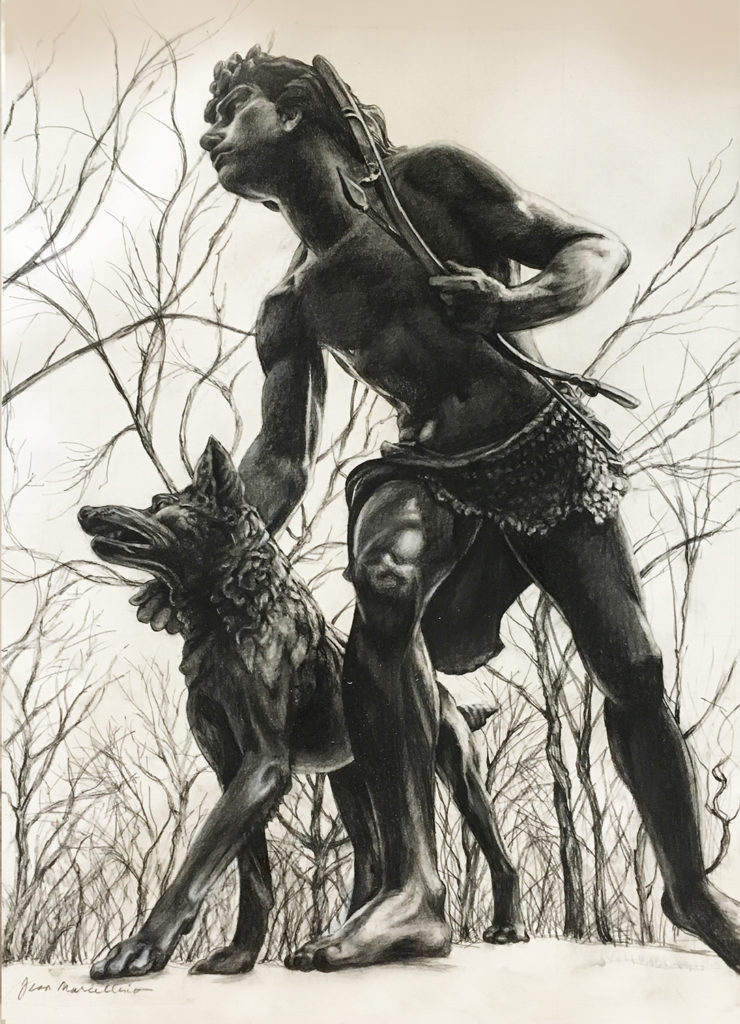

Indian Hunter

There are a number of sculptural works by John Quincy Adams Ward in Central Park not far from the Band Shell. This piece was created in 1866, and was the first statue erected in the park by an American. I drew this from an iPhone shot without the usual first step because it was too cold to sit there in winter. The Hunter seems perfectly comfortable in his bearskin.